From Spurious Correlations to Endogeneity

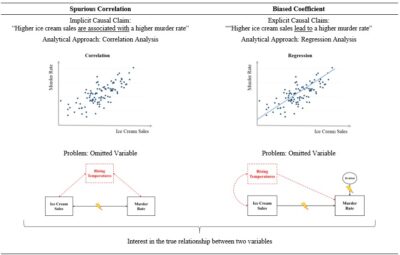

A good starting point for marketing researchers without a background in econometrics to understand the endogeneity problem are spurious correlations. Considering the well-known “eating ice cream leads to murder” example: A naïve look at the data would suggest a statistically reliable relationship (high correlation) between monthly ice cream sales and monthly murder rates. However, the relationship between the two variables is spurious because it is driven by a confounder—higher temperature in summer—which simultaneously boosts ice cream sales and, coincidentally, murder rates. There is an omitted cause for the observed relationship.

Spurious correlations and endogeneity are both concepts that contribute to misleading appearances of relationships within data. However, a key difference is in the inferred directionality of these relationships—whether variables are merely associated with each other (measured by a possibly spurious correlation coefficient) or whether one variable is thought to lead to the other (measured by a coefficient possibly biased by endogeneity). However, even if only an association is discussed, there is typically an implicit or explicit understanding of the directionality of variables. In our literature review, we observed that some authors stated that they only find a relationship in a non-experimental study although they have defined the predictor and outcome in a preceding hypothesis and used regression analysis to examine a directional effect. Being aware of these similarities and differences, the notion of a spurious correlation helps to understand endogeneity.

The General Endogeneity Problem

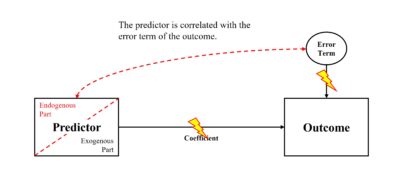

In its simplest form, regression analysis aims to assess the impact of one predictor variable on an outcome variable. This relationship is captured through the regression equation, which comprises an intercept (where the regression line meets the y-axis when the predictor equals zero), an estimated coefficient (describing the slope of the regression line for the predictor, which is the effect of the predictor and used for hypothesis testing), and an error term of the regression model, which includes all unobserved (or unmodeled) factors influencing the outcome. The essence of the endogeneity problem is that the estimated effect of a predictor on the outcome is biased because there is a correlation between the predictor and (at least) one unobserved factor that is part of the error term. However, the researcher faces a challenge as the error term is unobservable, which implies that there is no possible way to directly test whether it is correlated with the predictor, and hence to empirically rule out the threat of endogeneity. We note that the term “residual” is reserved for the estimated value of the error term (i.e., outcome minus predicted dependent variable), while the error term (disturbance term) is its theoretical, pre-estimation counterpart.

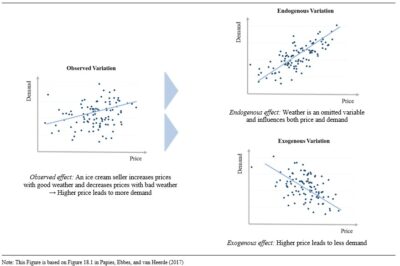

Consider the example of a smart ice-cream seller who knows that when the weather is good, there are more people on the beach, and these people are willing to pay more for ice cream. To take advantage of this behavior, the ice cream seller increases prices when the weather is good and decreases prices when the weather is bad. A researcher analyzing daily data about ice cream prices and ice cream sales would conclude that a higher price leads to more sales. However, the estimated price effect is biased because the weather is related to both prices and sales, not included in the model, and thus captured in the error term, which leads to a biased price effect.

In other words, the observed effect consists of two components: An endogenous part capturing the variation in the predictor that is correlated with the omitted weather variable and an exogenous part capturing the true causal effect of price on sales, as visualized in Web Appendix D. If weather is not accounted for, the estimated effect of ice cream price on ice cream sales (which combines the exogenous and endogenous parts) could be negative if the exogenous part dominates, positive if the endogenous part dominates, or zero if the exogenous and endogenous parts cancel each other out. Anyway, the estimated price effect will not reflect the true, unbiased price effect that would be observed in an experimental study with manipulation of the price. Thus, the data analysis would lead to erroneous conclusions about the price effect.

In this stylized example of an omitted variable the solution is obvious: collect data on weather and add this as a control variable. However, addressing endogeneity in a more realistic setting is not that simple as a researcher cannot readily observe all relevant omitted variables and because there are more complex sources underlying endogeneity, as we explain in the next section. Thus, the first step to address the endogeneity problem lies in detecting the sources that may lead to the endogenous part of an observed effect.